Introduction

The connection between sports and politics has never been more prevalent than it is today due to the power balance shift from hard power to soft power in contemporary geopolitics (Wagner 2014). Historically, many nations have attempted to use sport as a means for furthering political objectives and that trend is likely to continue throughout the 2020s and beyond. Recently, a new term has been used to describe these events: sportswashing. Based on the term ‘whitewashing’, the topic has become increasingly popular to the point where 2022 was considered ‘The Year of Sportswashing’ by Australian Outlook (Shelley 2022).

The act of sportswashing has been employed by governments throughout the history of sports, with one of the earliest and most significant examples coming in the form of the ‘Nazi Olympic Games’ held in Berlin in 1936. Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party used the Olympics to showcase the supposed ‘purity’ and ‘superiority’ of the Aryan race – furthering their political agenda for the years which followed. The regime used the Games to impress foreign spectators and journalists with an image of a peaceful, tolerant Germany, despite the atrocities and discrimination taking place under Nazi rule (Holocaust Encyclopedia 2023).

The use of sport as political influence is a contributing factor to ‘soft power’, which describes the aspects of a culture that impact geopolitical agendas (Næss 2023). Since sports provide such large and often international viewing communities, many countries wish to use them to promote their ideals to the world (Lewis 2015). Many countries have adapted to the new age of mass media consumption and have made investments into hosting sporting events, purchasing player contracts, sponsoring leagues, and purchasing teams (Considine 2023). Furthermore, scholars have noted different forms of sportswashing (Boykoff 2022), ranging from authoritarian to democratic, though they acknowledge that each situation is different and must be analyzed for their unique complexities.

Therefore, this study specifically examines the impact of sportswashing on the politics of authoritarian countries, with a primary focus on Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and China. To accomplish this, a qualitative research method was employed, utilizing one of the nine case study techniques established by Gerring (2017): the most similar technique. By comparing these countries that have employed sports for political purposes as a form of sportswashing, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon and its implications on both domestic and international politics. Ultimately, the goal is to validate the theory of soft power within each country’s individual context.

Literature Review

Soft Power Theory

Soft power has become an increasingly popular and important term to describe cultural and political actions which contribute to a country’s influence in geopolitics. The term was broadly defined by Joseph Nye (1990, p. 166) as, “When one country gets other countries to want what it wants.” This differs from traditional (hard) power, which Nye defines as, “The ability to get the outcomes one wants.” Both hard and soft power result in a country achieving favorable outcomes, but with soft power, all parties involved see favorable results instead of just the stronger party. This subtle difference contributes greatly to the methods countries use to apply each power method, causing soft power to be much more engrained into culture, holding long-term influence integral to the advancement of a country’s “milieu goals” (Nye 2004).

Nye’s 2004 book, “Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics” approaches power as a spectrum, ranking specific power-seeking behaviors from hard to soft power and corresponding them to resources likely to be used for each. For example, forced sanctions are seen as acts of coercion and are thusly considered hard power, while multilateral approaches to international issues are seen as attractive (co-optive) and are therefore soft power (Nye 2004). Nye’s argument poses that cooperation is better than coercion because it forms lasting relationships instead of short-term political wins. Government policies at home and abroad can also contribute to soft power, but due to contextual volatility, effects can vary over time. However, while these government-led programs promote a country’s goals, the mediums of export are traditionally separate from the government and are created by the culture instead of institutions.

Soft power is created by cultural integration of another country’s ideological values through the mass export of popular media, education, policy, and technology (Nye 2004). Nye argues that all examples of soft power fall under three ‘pillars’: culture, political values, and foreign policy. As a case that exemplifies the use of culture for soft power, Japan, which has been demilitarized after World War, has rebranded itself as ‘Cool Japan’ (Kelts 2006). Cool Japan refers to the strategy for promoting aspects of Japanese culture that foreigners view as ‘cool’ – fashion, anime, and unique cuisine, and it plays a central role in Japan’s global branding (Cabinet Office Japan 2018). Regarding political values, the spread of communism is a display of political values acting as soft power. The Soviet Union formed a strong bond with Cuba in the late 1950s due not only to its proximity to the United States but to its shared communist ideologies (Hershberg 2019). Of course, this example walks the line between soft and hard power because of the constant threat of a hard power attack. One of the most historically significant uses of foreign policy as soft power is the Marshall Plan. Following World War 2, the United States funded the economic recovery of Europe and strengthened relations with most of the continent while attempting to stop the spread of communism (Tarnoff 2018). We see the long term effects from the Marshall Plan’s soft power today as many consider it to be a catalyst in the formation of NATO.

Furthermore, sport is recognized as one of the most powerful and least talked about methods for soft power (Chan 2017) and numerous influential nations (e.g., the United States, the UK, China, etc.) have integrated sport to tighten their grip on global geopolitics, especially in the form of mega-events (Muller 2015). The 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics was seen an opportunity for Canada to advance their human rights agendas while driving their economy. The nation organized the first Pride House in Olympic history and signed agreements with First Nations representatives to promote advancements in the group’s culture and participation in sport (LeBlanc 2021). Canada was widely praised for the event and experienced favorability growth from 19/24 surveyed nations (LeBlanc 2021).

Like the example above, several countries have also utilized sports as a resource for soft power to achieve various purposes such as improving economic impact, national branding, and fostering international cooperation. One of these purposes involves diverting attention from their past transgressions, a practice commonly referred to as “sportswashing”.

Sportswashing: Concept and Background

Sportswashing refers to the practice of using sports events, teams, or athletes to divert attention from or improve the reputation of individuals, organizations, or countries that may be associated with controversial or negative actions (Chen and Doran 2022). The suffix ‘washing’ has been used to create new compound nouns describing perceived ill-actors in various ethical areas. The term whitewashing has been used in painting for hundreds of years but neologisms such as greenwashing, pinkwashing, veganwashing, and now sportswashing have all entered academic literature (Skey 2022).

Sportswashing itself was not academically defined until the mid-2010’s, but discussions about the concept have been growing in popularity since the 1990s. From 1990-2019, there were 4698 scholarly articles with the keyword ‘sport propaganda’ published compared to 1930-1989 when there were only 64 scholarly publications with that keyword (Skey 2022). The concept of sports propaganda has been associated with 20th century authoritarian sporting events, specifically the 1934 Italy World Cup and the 1936 Berlin Olympics. These events were utilized to propagate and legitimize fascist and Nazi ideologies and they provide a baseline for understanding modern sportswashing. The terms sportswashing and sport propaganda are not synonymous, but they share underlying concepts – primarily their correlation to reputation laundering and narrative control. In 2015, the term sportswashing was coined by Gulnara Akhundova in a newspaper article criticizing Azerbaijan’s hosting of the European Games, claiming sports caused the public to ignore their problematic human right situations (Akhundova 2015). Since then, sportswashing has become increasingly popular in academic discussion, growing from 269 news/academic articles in 2019 to 6,829 in 2022 (Ganji 2023).

There are also different types of sportswashing as described by the literature. Boykoff (2022) provides the most extensive figuring of contributing factors of sportswashing, demonstrating how international and domestic audiences contribute to the practice’s effectiveness. She has developed a typology of sportswashing, breaking examples of the concept down into the political context and the intended audience. The political context is the distinction between authoritarian or democratic sportswashing, while the audience is broken down into international or domestic (Boykoff 2022). While Boykoff does provide clarity on the topic’s forms, the term ‘sportswashing’ has a negative connotation; most people will not see the United States 2002 Olympics as sportswashing. However, according to Boykoff, the political motivation surrounding sport is the defining factor of sportswashing, not the perceived immorality of the government using it.

Though it is a newer term without a consensus definition, its core elements are consistent in corresponding literature to explain the relationship between sports and politics. Within the realm of sportswashing, it is evident that mega-event hosting nations and massive investment in sport are driven by political motivations, regardless of their democratic or authoritarian stances. The strategic utilization of sports as a cultural mediator has long served to promote a country’s political ideals and enhance its reputation, and the effects that sport has on political outcomes can be clearly seen once examined (Grix and Houlihan 2013, Meeuwsen and Kreft 2022).

The Relationship Between Sportswashing and Politics based on Soft Power

Sports and sporting events have been employed as soft power because they effectively promote a country’s political ideologies on massive scales. Over time, utilization of sport has evolved to encompass both domestic and international spheres, enabling countries to exert political influence on other nations and increase perceptions through sporting endeavors as a geopolitical strategy. Political objectives of sportswashing are contributed to directly by the country in their mega-event hosting methods and by non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) through the form of sponsorship.

During the early 20th century, national political power became seen more from the light of human resources, leading to an uptick in physical exercise programs in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the United States (Keys 2006). Early in the modern Olympics history, sporting success functioned from the view of belonging, Keys (2006, p. 8) noted: “For the great powers it became a matter of urgency to win more medals or more championships than rival powers. For the smaller nations it became critical not so much to win but to show up, to perform respectably, and to be seen as a member of the club.” This demonstrated the emphasis that countries placed on sport as a means of competing/existing on an international scale, and many countries invested heavily in these efforts. To be specific, countries have begun employing sport soft power methods to expand their political influence in various aspects of international and domestic conversation. In a modern domestic context, North Korea has used sport to promote their ideals to their citizens, Pinkston (2018, p. 1) describes their Olympic reintroduction motives, “for the domestic audience, the participation of North Korean athletes will provide examples of national pride and glory for which the party will take credit.” North Korea’s sport actions have had a positive impact on their relationship with South Korea, too, with Park et al. (2023) finding that the collaboration between the nations in the 2018 games decreased provocations and infiltrations between the nations.

In the international context, Qatar has emerged as a prominent player in modern sport soft power initiatives, employing various methods to establish and strengthen its position. Notably, Qatar held the 2022 World Cup, but they have also made substantial investments using state funds in the media outlet Al Jazeera and the airline carrier Qatar Airways. These strategic investments have provided the necessary rhetorical framework to support the country’s objectives and to gain recognition as a dominant force in the Middle East despite many nations cutting ties due to alleged support of Islamist terror groups, among other perceived immoral actions (Brannagan and Giulianotti 2018). Furthermore, Qatar has become an international hub by hosting other major sporting events such as the 2011 Arab Games and the 2019 International Association of Athletics Federations World Championships. Qatar Airways has also been a major sponsor throughout the world of athletics, finding sponsorship deals with FIFA, Bayern Munich, the Indian Premier League (cricket), and the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets, among others. This study further explores Qatar’s efforts during the case study portion of this paper, but for now, the information provided will suffice.

As examples of the political context in sportswashing, Boykoff (2022) cites the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics as an instance of democratic sportswashing, where the United States utilized the mega-event to promote their security in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. This example demonstrates the variability of approaches in sportswashing where the promotion of ideological ideals is very apparent. On the other hand, Almog et al. (2013) discussed the nature of the sportswashing in the authoritarian sportswashing context, highlighting fascist media interpretations of games and limited access to viewership as factors that contributed to Italy’s positive image following their home World Cup victory in 1934. Furthermore, Fruh et al. (2023) provides a definition of the three potential outcomes of sportswashing in the context of the 2022 World Cup hosted by Qatar. These outcomes include: (1) distraction from moral violations, (2) minimizing the significance of such violations, and (3) normalization of these violations. This contemporary context sheds light on the authoritarian methods employed in sportswashing.

Like above, several nations opt for soft power initiatives to strengthen their diplomatic influence over years or even decades. Wagner (2014, p.1-2) argues that a key difference between hard and soft power is time, stating, “…soft power takes relatively long to build as its intangible resources develop over a long period of time.” Countries willing to invest time into soft power methods of diplomacy have seen wide reaching benefits in their political influence, and sport-related methods create wide-spanning influence for power-imposing countries. The methods used for cultivating soft power via sportswashing can be seen from several lenses and each sportswashing scenario must be examined thoroughly to be understood.

The Question of the Effect of Authoritarian Sportswashing on Politics

Based on the theory of soft power, the literature on the relationship between sportswashing and politics, and the different political types of sportswashing, it is evident that mega sport events held by democratic countries (such as the United States, England, Spain, Japan, South Korea, etc.) and professional sport leagues operated by them have clear political purposes and impacts. These purposes typically include enhancing national pride, reputation, economic impact, fostering international cooperation, and increasing political legitimacy (Storm and Jakobsen 2019).

However, in the context of authoritarian countries (such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, China, North Korea, etc.), their genuine political purposes of utilizing sport remain unclear because authoritarian sportswashing attempts often aim to conceal their misdeeds and tend to be perceived as a disruption to the integrity of sports. According to Dun et al. (2022), research conducted on perceptions of Qatar on Twitter found that their host nation status “has not necessarily brought better nation branding or enhanced soft power,” though Twitter is not the most reliable source when discussing academic topics. So, in order to gain a clearer understanding of the effects of authoritarian sport-related soft power on politics, this research investigates several cases of authoritarian sportswashing.

Research Question: Does authoritarian sportswashing have an impact on political objectives as a form of soft power?

To find an answer to the question, it must first be acknowledged that each authoritarian country has different situations and motivation to start their sportswashing. So, a qualitative research method is employed. China and Qatar’s most recognizable sportswashing attempts occurred on single, large-scale events (Brannagan et al. 2019) while Saudi Arabia has not yet had any mega events. However, Saudi investment into the sport sector is more diversified than the others and is more invasive into western sports leagues (Salao 2023). To answer to the research question rationally, this study examines the effect of different factors of the authoritarian countries (e.g., the amount of investment and the diversification of sportswashing activities…) on the outcomes of their sportswashing, and the author establishes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: Authoritarian countries with higher levels of investment and a broader range of sportswashing initiatives will experience more significant outcomes and perceived success in their sportswashing endeavors.

Methods

Research Design

To properly understand the political impact of sportswashing, this study utilizes a qualitative research method, specifically a case study approach, to examine multiple cases across numerous countries. For this research, the most-similar method is adopted among the nine-case study techniques developed by Gerring (2007). This method aims to examine the precise geopolitical context of each country by studying the history of their sportswashing and utilizing secondary data. The countries that were examined as cases in this study are as follows: China (2008-2022), Qatar (2006-2022), and Saudi Arabia (2016-2024).

Figure 1. The research framework of the most-similar analysis

Note. The figure is sourced from Gerring. (2007, p. 132)

Specifically, the most-similar case method needs a minimum of two cases or more and has an exploratory-style structure (Hypothesis-testing structure) as shown in Figure 1. Researchers who use this method need to look for various factors (independent variables, X1) in similar cases that can contribute to the outcomes of theoretical interest (dependent variables, Y). Like the name of the method, furthermore, the backgrounds or situations of the cases chosen in this study should be similar, which is the control variable (X2).

The authors consider the three cases: China, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, similar because they have ‘authoritarian leadership,’ which will be the control variable (X2) of this study. To reliably confirm if those countries have authoritarian leadership, the Democracy Index (TDI), reported by Economist Intelligence (2009, 2023), was used. TDI is an annual study in which experts are asked to rank each of the 167 countries provided by their democratic performance in several areas. Each of the countries researched falls beneath the ‘Authoritarian Regime’ status in the index, having scores less than a cumulative 4.0 out of 10.

Various factors (independent variables, X1) in this study that may have affected the outcome are the scale of each country’s sportswashing attempt. This scale can include the amount of investment made for sportswashing purposes, the diversification of sportswashing activities, or other factors. However, accurately measuring the exact dollar amount invested in sportswashing activities is difficult – if not impossible – to accomplish because of a lack of financial disclosure and overall top-down secrecy from these nations. While the findings discuss dollar figures, there will not be any compiled numbers claiming exact figuring. Although these terms may lack precise clarity, they will be validated within the context of the findings. Regarding the diversification of sportswashing activity, it includes the number of sports or types of sports in which each country invested or engaged. This encompasses activities such as sponsorships of sports leagues/clubs, state-funded soccer club player purchases, event infrastructure construction, hosting of events, organizing mega sport events, and so on.

Lastly, the outcomes of sportswashing (dependent variable, Y), as identified by Wu (2017), include the coverage of sportswashing by foreign media, the viewership of each sportswashing attempt, or the growth rate of tourism. Based on these variables in the research framework, the hypotheses are examined and judged based on Wu’s Soft Power Rubric. Additionally, due to the challenge of precisely measuring the independent and dependent variables, the variables are assessed using terms such as ‘least,’ ‘average,’ and ‘most.’ Although these terms may not offer precise clarity, within the context of the findings, they are validated and considered valid indicators.

Figure 2. Wu’s Rubric for Soft Power

Note. This figure is sourced from Wu 2020.

Validation checks for cases are an important consideration in case studies. It is crucial to determine whether the research design is valid by assessing if the cases exhibit either temporal or spatial variation. Temporal variation, as defined by Gerring (2017) and used by Park et al. (2023), involves comparing changes over time within the same country, such as comparing mega sport events in South Korea in 1984 and 2018. On the other hand, spatial variation refers to comparing cases across different countries during the same period. In this study, the cases of China, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia occurred in a similar time period (the beginning of the 21st century) but in different countries, aligning with the spatial variation approach. Therefore, the validation of the cases in this research qualifies them for the next step, where we can explore the likelihood of hidden complexities arising from complicating factors within the theoretical framework.

Findings

China

China is described as a country having an authoritarian regime where Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rules, “…all aspects of life and governance, including the state bureaucracy, the media, online speech, religious practice, universities, businesses, and civil society associations,” (Freedom House, 2023). Furthermore, Xi Jinping, the leader of the CCP and the nation’s president, has increasingly consolidated and expanded his dictatorial and political power since March 2013. Recently, the CCP’s suppression of political dissent, human rights advocates, and independent non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as the crackdown on civil society, has had a significant impact on China’s civil society, causing considerable devastation (Freedom House, 2023). To enhance the reliability of such situations as authoritarian, it is important to consider that China’s cumulative score on TDI for 2022 is 1.94 (Democracy Index, 2022), placing it below 4 and classifying it as an authoritarian country.

Beijing was the first city to host both the Summer and the Winter Olympic games, in 2008 and 2022 respectively (Meng & Neto). China’s 2008 Beijing Olympics acted as a stage for China to promote their newly technologically developed nation to the rest of the world while attempting to rebrand (Zhongying 2008). There was a reported $42 billion in infrastructure invested into the 2008 Games (Fowler & Meichtry 2008) and approximately $40 billion into the 2022 Games (Teh & Stonington 2022). These massive investments provided positive outcomes for citizens and created a positive environment for viewers. At least, 2008 did, 2022 was not nearly as well received in foreign media (Adgate 2022).

In line with their authoritarian leadership style, several stories about Chinese mistreatment of Tibetans came out in 2008 (HRW 2008), staining their public reputation and bringing travesty to light just months before the Olympics. During this time, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) faced significant pressure but ultimately kept quiet (Brownell 2012). Similar can be said for the 2022 games. Since 2014, the Chinese government has been incarcerating hundreds of thousands of their Muslim minority population in what the U.S. considers a genocidal fashion (Maizland 2022). Having the games has brought more conversation to these topics, calling China’s reputation into character and reinforcing negative perceptions from western nations (Sin 2022).

As an outcome of the games, there was significant short-term attraction, with consumption of the media being the most prevalent; 4.7 billion people viewed at least part of it, making it the single most heavily consumed mega-event in history at the time (Geurin & Narine 2020). However, continuing down the rubric, China did not perform well with the other steps. While Wu’s examples of further steps; ‘study abroad’ and ‘emigration’ are not relevant in this case, ‘visit a country’ is extremely valuable. Comparing relative tourist levels can provide some insight into the effectiveness of their soft power choice. There was a significant decrease year-over-year for foreign tourists (Zhou and Singh 2015) in Beijing in 2008 and only those who met very specific requirements were allowed in 2022 due to strict COVID-19 restrictions (Barrett 2021).

In the time between Olympics, China attempted to utilize their sports leagues as ways to increase international interest by purchasing players for extremely high sums (Crabtree 2016). Their basketball league initially experienced positive foreign involvement: an influx of former NBA players has gone to play in the league (Zwerling 2013). However, the league was not regarded highly in terms of competition, falling 12th in ESPN’s ranking (Fraschilla 2017). China still pays many basketball players more money than any other league in the world apart from the NBA (Neumann 2017), and there is clearly still a high-value market for basketball in the country.

China had objectives of increasing the internal development of sport at this same time, too, hoping to transition into Asia’s soccer powerhouse by 2030 and the world’s best team by 2050 (Campbell 2016). Businessmen from the country took up similar investment in sport, purchasing varying shares in numerous clubs in Europe during the 2010s (Slater 2020). However, following many devastating losses for the Chinese Men’s National Team, and a lack of financial returns (Panja 2023), the Chinese government forced investors out of European leagues. Like their basketball league, they infused foreign talent into many teams, investing hundreds of millions into star talent. Most of the foreign players from the soccer league have since retired or left the country (Panja 2023) and the basketball players have continued to transfer leagues.

China’s soft power sports initiatives have proven fallible which is consistent with their performance in the TDI. By not having returns on investment, sports leagues and clubs as tools for soft power were not viable or sustainable for the Chinese government. Compared with Qatar and Saudi Arabia who have much higher GDP’s per capita (World Bank 2023), China needed to be much more efficient with their sportswashing, and while it may have cultivated soft power in the short term, purchasing of clubs and players was not realistic for long term success. The 2008 games did provide extensive viewership, but the 2022 games did not, consistent with the disinvestment in sports in the nation. China’s sports soft power initiatives may have been initially effective for drawing viewership, as time progressed, their investments became less lucrative, finally causing less foreign investment in sport.

Qatar

According to Freedom House (2023), Qatar is classified as an authoritarian country, and it’s TDI score verified that claim: 3.65/10 and 114th of 167 nations ranked. It is governed by a hereditary emir who holds control over all three branches of the government: the executive, judiciary, and legislative authorities. Additionally, political parties are not permitted to be established in Qatar. Furthermore, the majority of the population in the country generally lacks political rights, experiences limited civil liberties, and has restricted access to economic opportunities. In terms of their domestic politics, their policies on LGBTQ+ individuals remain outdated, and the nation punished those who wore supporting arm bands and arrests openly gay individuals (HRW 2022). The nation has failed to adapt to modern times and remains very conservative in their policy on the subject, as have most nations which enable Sharia law (Crary et al. 2022).

Financially, Qatar is one of the richest nations in the world per capita due to the country’s extensive oil fields (IMF 2023) and many state-funded companies have been created with this surplus. The nation uses its intense capital to cultivate soft power through the means of sporting events and has been doing so for nearly two decades, culminating in the 2022 World Cup. However, critics of Qatar have often cited the migrant deaths involved with the World Cup as a primary example of Qatar’s need to sportswash. The country also has ties to terrorist organizations and from 2017 to 2021, a Saudi-led coalition severed relations with the state for that reason (Roberts 2017). When discussing the use of sportswashing to compensate unethical and negative images created by authoritarian politics, Qatar has hosted dozens of events (Clarey 2014) while sponsoring various clubs and leagues in the process.

Their hosting of the 2022 World Cup follows a logical progression of event hosting dating back over a decade; the nation has hosted many events that they discuss heavily on the ‘VisitQatar’ website, (Visit Qatar 2023) including many annual events. Perhaps the most notable of these early events was the 2006 Doha Asian Games where Qatar became the first Gulf Nation to host the event (Amara 2011). These games provided a platform for the country to begin modernizing and growing into the new century while adapting for their ever-changing soft power situation.

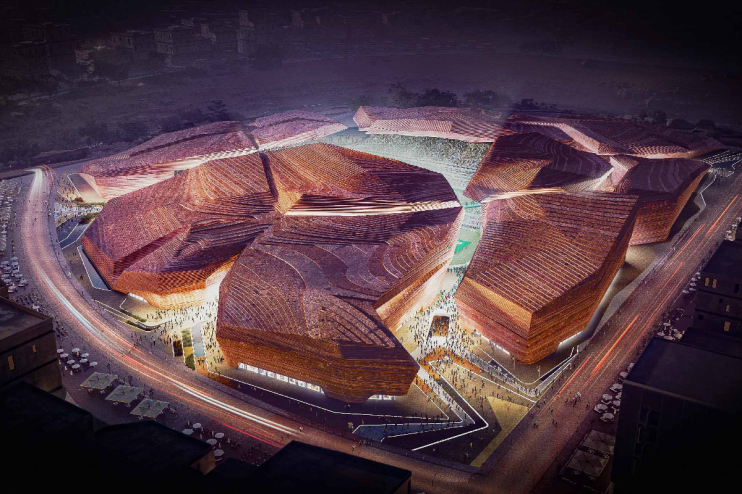

Prior to these Asian Games, in 2005, Qatar Sports Investments (QSI) was founded as a subsidiary of the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), the country’s sovereign wealth fund (WEF 2023). This investing body is used to increase influence in world sport and is owned by Qatari royals interested in serving the best interest of their country, supporting their country’s major goals (Ganji 2022). This major goal is called ‘Vision 2030’ and it will be further discussed in regard to Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Investments continued and the state made bids for mega events (Reuters Staff 2012) until in 2010, the state was awarded the 2022 World Cup, giving the Qatari government 12 years to progress their state’s infrastructure and sporting venues. The country invested a reported $220 billion in infrastructure to prepare, the most of any nation for any mega-event ever (Craig 2022). Calculated as a percent of GDP for that period, that is 10.2% per year.

In 2011, the gulf nation took a further interest in soccer, acquiring Paris Saint-Germain which has become a beacon of soft power in continental Europe (France-Presse 2023). The country’s soccer investment was not limited to France, however. The QSI has also purchased majority ownership in S.C Braga of Portugal. Furthermore, state-funded businesses have investments in over 140 sport-related businesses or organizations (Olsen 2022), influencing and branding the nation across the globe. Qatar Airways is a primary sponsor of 17 different sports, be it clubs or events within them (Olsen 2022). Qatar’s national team is becoming increasingly successful, too, winning both the 2019 and 2023 AFC Asian Cup.

Moreover, foreign tourism drastically increased during the World Cup and the months following. In the first two months of 2023, Qatar experienced an over 300% increase in tourism (Fast Company Staff 2023). The tourism market is a prominent source of income for the Qatari government, providing 7% of the nation’s GDP in 2019 while projecting to take up 12% in 2030 (Godinho 2022). Much of this seems related to their decades-long strategy of using sport in connection with tourism, enhancing their reputation in the process.

Regarding the outcomes of political interests caused by their sportswashing, the World Cup was one of the most viewed mega events ever and the country exceeded tourist expectations during the event, drawing in over 5 billion engagements and 3.4 million spectators (InsideFIFA 2023). FIFA also complimented the event, calling it the “…best World Cup ever,” (AlJazeera 2022). Having these compliments has created an environment in Qatar where more events are likely to be given. There were attempts to host the 2016, 2020, and 2032 Olympic Games, and the small nation is hoping to host the 2036 Olympic Games in Doha (Poindexter 2022). The state will host the 2030 Asian Games in Doha (AP 2020), bringing the event to the Persian Gulf for the time since the 2006 games, and they have held other significant Asian events including the 2023 AFC Asian Cup. Corresponding to their Vision 2030 objectives, the 2030 Asian Games will demonstrate Qatar’s prosperity and reformation throughout the past decades and will be a key to their soft power objectives in Asia (Alloul 2023).

An interesting point to note before continuing to Saudi Arabia is the Qatar diplomatic crisis, and this study would not be complete without ample analysis of the incident. As alluded to earlier, from 2017 to 2021, there was a widespread deterioration of diplomatic relations between Qatar and many members of the Arab League, led by Saudi Arabia. To fully understand the implications of this incident would take ten thousand more words, but in broad terms Qatar allegedly harbored terrorist groups, causing Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt to simultaneously cut ties with Qatar, forming a de facto blockade on Qatari transport (Ramani 2021). This impacted their airspace, and thus weakened Qatar Airways, and therefore their economy. Their GDP declined year over year during this time, and the implied lack of regional unity would not have been a positive influence on the soft power displayed in the World Cup (Buigut & Kapar 2020). In January 2021, a deal was brokered to reopen the Saudi Arabian – Qatari border. To say that the World Cup was the sole motivator for the deal would be biased speculation and incorrect, but to neglect its impact on the situation is just as irresponsible.

Saudi Arabia (KSA)

The authoritarian markings in KSA are quite apparent and involve world geopolitics more than Qatar. Freedom House (2023) describes Saudi Arabia as follows:

“Saudi Arabia’s absolute monarchy restricts almost all political rights and civil liberties. No officials at the national level are elected. The regime relies on pervasive surveillance, the criminalization of dissent, appeals to sectarianism and ethnicity, and public spending supported by oil revenues to maintain power. Women and members of religious minority groups face extensive discrimination in law and in practice. Working conditions for the large expatriate labor force are often exploitative.”

Specifically, the state was reportedly involved with the 2017 murder of American journalist Jamal Khashoggi, causing severe international backlash (Milanovic 2019). The country has also engaged in a war with neighboring country Yemen, contributing to death and famine in what many consider the worst active civil war (Darwich 2018). The Yemen conflict, like many of the topics mentioned in this study, requires its own research paper, but put simply, the Saudi involvement did not improve the situation. Their conservative stance on women’s rights has been notable as well, but the regime is making strong efforts to change that narrative through new policy (Azimova 2016). Their TDI in 2022 is 2.08 out of 10, indicating that they are indeed categorized as an authoritarian leadership country according to the Democracy Index (2022).

Since 2016, the country has begun diversifying their economy away from oil, expanding their tourism sector (Khan 2020) and spending significant money on sports through Vision 2030 objectives. Saudi Arabia, like Qatar, has a sovereign wealth fund at its disposal which its leader, Mohammad Bin Salman, has supreme control over, while it claims to be separate from the state (D’Urso 2021). It contributes to their much larger Vision 2030 mission which was announced in 2016 (Vision 2030 2021). With Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, strong emphasis is put on increasing tourism (Saudi Tourism Authority 2023) and privatized sport investment is being used to accomplish these goals.

Privatized sports investments in the nation are made with the Public Investment Fund (PIF), Saudi Arabia’s version of the QIA. The PIF is projected to be the world’s largest wealth fund by 2030 and is gaining new investors to make this vision a reality, further driving their Vision 2030 objectives (Alqahtani 2023). The PIF is the strongest tool Saudi royalty has used for enacting their will upon the sports world. PIF investments include Newcastle United, LIV Golf (terms of PGA sponsorship and merger currently unknown), the WWE, Boxing, Formula 1 and other racing sports, and numerous domestic clubs in the Saudi Pro League (Elsborg 2023). These clubs have made purchases of their own; Al Nassr signed Cristiano Ronaldo for a reported 2-year, $400mn deal, though sources are inconclusive on the true contractual terms (Noble et al. 2022). Attendance for the Saudi Pro League, host league of Al Nassr, has increased by 147% since the signing. Several other league and player-based investments have been made by Saudi Arabia (Smith 2023) and the nation is showing clear interest in shaking up international sport. Their investments in players mirrors China’s, offering massive contracts (Acosta 2023, Piastowski 2023) to athletes in multiple sports. Where they differ, however, is the number of sports that they are invested in and the methods they use in each.

Perhaps their most telling investment is the LIV Golf league, a direct competitor to the PGA. The league began in 2022 with 48 players competing for the highest paying per-player golf purses of all time (Byers 2022). The players were also provided with signing bonus money, further incentivizing a move of tours. However, the league made little revenue (Beall 2023), has performed poorly in the television ratings (Colgan 2023), and is involved in ongoing lawsuits with the PGA. Despite these limiting factors, the league unexpectedly announced a merger with the PGA and DP World Tours in June 2023 (Rizzo 2023) with the PIF as the leagues ‘primary investor’. There has been much talk about a potential PIF investment in a rival tennis league (Wetheim 2023), which, while just speculation, still seems likely, as does further investment in other rival leagues for major monopolized sports.

On an event hosting level, the country is taking inspiration from Qatar, hosting and sponsoring mega-events (O’Donnell 2023) while developing infrastructure for the future. In terms of verifiable future events, Saudi Arabia will be host to the 2029 Asian Winter Games and the 2034 Asian Games, some of the largest multi-sport events besides the Olympics (Hindustan Times 2018). They were also the only nation to submit a bid for the 2034 World Cup, and they are slated to be the host nation. This is where an overwhelming majority of Saudi Arabian sports investment is currently directed, and the nation is attempting to connect sport with tourism. Trojena is the host ‘city’ for the 2029 Asian Winter Games and will be a year-round skiing destination and resort in the mountains of Saudi Arabia, once complete in 2026 (NEOM 2023). Trojena contributes to the larger $500bn NEOM project which Saudi officials claim will be 33 times larger than New York City and completely operated by clean energy (NEOM 2023), a stark contrast to the old Saudi Arabian brand founded on oil. On top of that, they were the fastest growing tourist nation in the G20 in 2022 and have experience tremendous growth in tourism since opening the country to foreign visas in 2019 (Saudi Tourism Authority 2022). The tourism growth is likely to continue as more destinations open and more projects are completed. The nation hopes to have 10% of its GDP in tourism by 2030 compared to 3% right now (Wald 2019). The connection between sport and tourism is incredibly apparent in Saudi Arabia and is a defining characteristic of their future intentions.

Overall, the current value of the sport-related investments, infrastructure and other, made so far by Saudi Arabia is over $100 billion and they are only in their seventh year of Vision 2030. While total sport-related infrastructure costs depend on many factors, the future events slated for the late 2020’s and early 2030’s increase the likelihood for consistent investment. Tourism growth has been quite prominent during the Vision 2030 era of Saudi Arabia, and it will likely continue to be. As of February 2024, Saudi Arabia’s sportswashing has been successful, and the following ten years will be instrumental in determining the soft power implications of their current work.

Discussion (Implementation) & Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to understand the effect of sportswashing on politics based on soft power theory, but once sportswashing is understood, other geopolitical relations seem to fall into place. By comparing the three authoritarian country cases, this study finds that the investment and diversification of sportswashing affects the outcomes of their sportswashing and politics. Based on the findings from the two cases, Table 1 is established.

Table 1. The effect of sportswashing on the outcomes

| Case types | X1 | X2(Control Variable: TDI) | Y (The outcomes) | |

| Investment | Diversification | |||

| Saudi Arabia | High | High | 2.08 | High |

| Qatar | High | High | 3.65 | High |

| China | Low | High | 1.94 | Low |

The modern era of geopolitics amongst competing governments has evolved with the use of soft power, using sport as an often unthought-of but primary factor in its cultivation. Sport and tourism are tightly paired when analyzing soft power’s effectiveness, and it is apparent that their effects can be felt through mega events and sponsored investments. Each case studied makes similar investments, but as explored, there are many limitations each country has had in doing so.

Sport is being used much more commonly by authoritarian countries to promote nationalistic views which may not always be the most accurate in the larger geopolitical landscape. International governing bodies have shown apprehension to step in (Mukund 2022), neglecting to make denouncing statements and providing the countries with platforms to engage in sportswashing.

It would be poor academia to write all actions off as simply ‘sportswashing’ for the sake of reputation laundering because each country is using sport with different motivation (Bryder 2001) and there is more to each situation than simply sport. Saudi Arabia is attempting a country rebrand as laid out in the Vision 2030 objective (Vision2030 2021) and it is using sport as a key to cultivate the soft power necessary to do so. They also have clear priorities to trump Iran in the proxy war for the Middle East. However, the rebrand seems genuine, despite their current disposition towards democracy; so, is it really ‘authoritarian sportswashing’ in a traditional sense? Qatar’s use of Vision 2030 is ten years advanced from Saudi Arabia’s which provides a framework for potential investments. Qatar has been relatively successful in rebranding thus far in Vision 2030 and has been a mediator in several international conflicts and disputes. Both countries are using these plans to boost foreign tourism as well. The World Cup’s popularity drew in exponentially more foreign tourists (Aguilar 2022), and it served as a capstone for 20 years of sportswashing.

China has fallen back as a lesser competitor in the sportswashing scene due to their lack of disposable income, but during the 2008 Olympics, they held immense capacity for soft power. They were involved in an economic and technological revolution (USCBC 2008) which they had attempted to combine with a reformed, more democratic attitude. Their continuation of authoritarian actions made their previous claims less significant and caused the rest of their sportswashing attempts to fail, along with their lack of access to a sovereign wealth fund. China’s fall in the Democracy Index demonstrates the effects of incorrect procedure when using sport as soft power.

There seems to be a clear progression in Saudi Arabia’s sportswashing attempts, very similar to that of Qatar’s, which build into the 2029 Asian Winter Games, 2034 Asian Games, and the 2034 World Cup. The World Cup in 2034 will be the defining moment of their sportswashing. They will demonstrate to the world a ‘New Saudi Arabia’ that is technologically advanced, inviting, culturally dense with tourist destinations, and socially reformed (Zhavoronkov 2022)) much like that of China in 2008. The mega-events will cultivate extreme regional soft power in the Persian Gulf and the continent of Asia, and the leagues they are investing in will continue succeeding, given the PIF has enough disposable funding.

What this study provides is a logical prediction of the progression of their sportswashing based on the qualitative evidence of other cases. Qatar has invested in sponsorship and event hosting but is not a large enough market to host quality leagues; however, that sponsorship has not gone away, and their social power is increasing through the help of the QIA. Saudi Arabia and China have both invested in bringing players to their leagues, but their situations are very different, and their timelines are nearly a decade removed. Monetary limitations proved too immense for China’s investing body to maintain club and player investment, so the nation had to suspend much of their international investment. Saudi Arabia’s PIF provides much more leeway with funding sports operations and their market size provides the ability to invest in soccer athletes for their leagues. China’s outcomes decreased drastically in the years following their usage of sports due in part to the massive spotlight placed on them during the Olympic Games. When countries expose themselves to such high viewership, they are more likely to be exposed for any perceived flaws in their system, infrastructure, or in China’s case, human rights violations.

Saudi Arabia’s investment of sport is likely to continue given the increase in tourism, the necessity of preparation, and the success of their previous investments, though the latter is yet to be proven extensively. By taking the other examples and comparing their effectiveness, we can logically infer the continuation of Saudi Arabia’s utilization of sport, yet the democracy index has shown no improvement in the country’s status. Qatar saw great leaps in their TDI score over their sportswashing timeframe, and it seems likely that similar results may happen with Saudi Arabia. If Saudi Arabia wants their sportswashing to be optimally effective, they will need to adapt their policy as well. Social conservatism is being phased out of world politics, especially former Islamic norms regarding women (Offenhauer 2005). The nation is at a crucial stage because it can choose to either continue their authoritarian rule or evolve into a modernized nation. And it appears that they would prefer the latter with their commitments to renewable energy (Lo 2021) and future sport. With the impending elimination of oil in the gulf nations, the need to diversify national investment is imperative, and sport is a key part of the plan to do so. Qatar and Saudi Arabia are using sport as soft power effectively, given the links between sport and tourism (Fourie & Santana-Gallego 2011). More investment will be made in the future, and it will take time to see the implications mentioned in this study, but the objectives are clearly presented by Saudi leadership (Mathews 2021).

The future of sports will be linked to sportswashing practices for the foreseeable future as more countries employ soft power tactics as means for diplomacy in contemporary geopolitics. The countries examined have provided qualitative evidence for effective and ineffective sportswashing approaches and shows a brief history on some of the countries which have engaged with it. It remains to be seen how the current world sports landscape will change in the coming years, but it is clear that several authoritarian countries wish to use it for various motivations, all of which contribute to their country’s soft power.

Limitations

This case study is limited in numerous areas incidentally caused by the differences of the cases, specifically the timeframes studied and the geopolitical situations of each timeframe. China and Qatar both have extensive histories of sportswashing and therefor can be researched for those longer periods of time, but Saudi Arabia has only been sportswashing since 2016, and only more recently has increased the project investment to a notable international level.

It is also quite difficult to accurately quantify the value of each country’s sport-related infrastructure investment. Saudi Arabia provides an interesting example for this; their NEOM Megacity features a ski resort – Trojena – that will be host to the 2029 Asian Winter Games (OlympicTalk 2022). However, it is also designed to be a tourist hotspot which begs the question: what is the true sport-related investment cost? The total NEOM investment is projected to cost $500 billion, but there are no official figures for Trojena. However, there are four regions of NEOM, so for the purpose of this study, 1/4 of the NEOM cost will be included in the final figuring. For China, all event-related infrastructure costs have been dictated as ‘sport-related’, corresponding to the $220 billion infrastructure-heavy investment Qatar made for the World Cup (Craig 2022).

While all the investment values listed in this study are accurate as reported by new agencies (Summerscales 2023, Thapa 2023, Fowler & Meichtry 2008) there are still many investments that must be estimated. This eliminates the ability of this study to use quantitative values when discussing individual countries, but they can still be mapped qualitatively, as this study attempts to adapt for. While observational evidence is interesting, it is still subject to bias is source selection (Infante-Rivard & Cusson 2018) and the potential for missed information.

The vast use of sponsorship provides another need for estimation, further limiting the quantitative findings this study had initially intended for. The ‘total investment cost’ variable must be estimated and there must be an additional ‘uses sponsorships=yes/no’ comparison. In the case of Qatar, there is accurate information (Olsen 2022) about many of their government-owned companies’ investments in sports, but the same cannot be said for Saudi Arabia. Their sovereign wealth fund owns, co-owns, or invests in companies across markets with variability in size (Hafiz 2023, Bahceli & Saba 2023) and influence. Also due to their delineation as private sector companies, the precise dollar values for each investment are not always publicized, causing severe estimation to be made (Rashid et al. 2019).

Furthermore, Saudi Arabia, is continuing to make multi-hundred-million-dollar investments in numerous sports (Whitehead 2023), and they show no signs of slowing down (Rizzo 2023) makes it even more difficult to quantify their current investment size, let alone predict their future in sport. This study will attempt to make predictions based on the other cases, but there cannot be confidence intervals for such broad, non-number variables. They may follow a path as predicted in this study, but the act of prediction is obviously fallible, and it should be used cautiously.

Another limitation in this research is the difference in the timeline of each country. While that does provide interesting insights for potential results of other countries taking similar approaches, geopolitical influences are different across time periods. The COVID-19 pandemic affected the Beijing 2022 games viewership and tourism (Guzman 2022) whereas other countries may not have felt the effects during their events, depending on case.

This study examines the situation from numerous points of view but does not have any real-world interpersonal data from consumers. As previously mentioned, there have been Twitter examinations (Dun et al. 2022) but that is different from the survey data necessary for understanding. In an ideal follow-up study, there would be high N survey data to track the perceived effectiveness of each countries soft power methods more accurately, focusing on individual interpretations of media from regionally specific consumers, determining their likeliness to engage in soft-power-specific activities.

It is difficult to curate a high-quality piece of academic literature when the subjects are of such size and complexity but given the scale of context covered in this study, the author believes that there is value in the information conveyed. The overall geopolitical context in world politics is much larger than simply which sporting event is held by whom; however, sport’s role is important to examine as it is a contributing factor to a country’s soft power both now and in the future.

References

Acosta, J. (2023). Karim Benzema’s new Saudi Arabian soccer deal is worth 4x more than any American athlete. SBNation. Retrieved from: https://www.sbnation.com/soccer/2023/6/1/23745478/karim-benzema-contract-saudi-arabia-soccer-deal-american-sports

Adgate, B. (2022). TV Ratings For Beijing Winter Olympics Was An All-Time Low; For Streaming It Was An All-Time High. Forbes. Retrieved from: TV Ratings For Beijing Winter Olympics Was An All-Time Low; For Streaming It Was An All-Time High (forbes.com)

Aguilar, J. (2022). Qatar’s tourism sector reached new heights during 2022. Gulf Times. Retrieved from: https://www.gulf-times.com/article/652241/qatar/qatars-tourism-sector-reached-new-heights-during-2022

Alghoul, M., Al-Hitmi, M., Hassan, Q., Jaszczur, M., Salman, M.H., & Sameen, A.Z., (2023). Energy futures and green hydrogen production: Is Saudi Arabia trend? Results in Engineering, 18.

AlJazeera. (2022). FIFA chief praises Qatar 2022 as ‘best World Cup ever’. AlJazeera. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/sports/2022/12/16/infantino-qatar-2022-best-world-cup-ever#:~:text=Infantino%20hails%20%27transformative%20legacy%27%20of,a%20nod%20also%20to%20Morocco.

Alloul, J. (2023). Qatar’s West Asian Moment: The Geopolitics of the World Cup. Foreign Policy Research Institute – Middle East Program. Retrieved from: https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/03/qatars-west-asian-moment-the-geopolitics-of-the-world-cup/

Almog, H., Anspach, E. & Taylor (2013). The 1934 World Cup. Duke University. https://sites.duke.edu/wcwp/research-projects/football-and-politics-in-europe-1930s-1950s/mussolinis-football/the-1934-world-cup/

Alqahtani, T. (2023). The persuasive use of public relations in Saudi Arabia 2030 vision. Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University.

Akhundova, G. (2015). Baku European Games 2015: A fearsome PR machine is using sport to sweep human rights under the carpet. Independent. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/baku-european-games-2015-a-fearsome-pr-machine-is-using-sport-to-sweep-human-rights-under-the-carpet-10314316.html

Amara, M. (2011) 2006 Qatar Asian Games: A ‘Modernication’ Project from Above? Taylor and Francis Online. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430500249217

Aramco. (2023). Global presence. Aramco. Retrieved from: https://www.aramco.com/en/who-we-are/overview/global-presence

Azimova, Amalkhon Y. (2016). Political Participation and Political Repression: Women in Saudi Arabia. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1186.

https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1186

Bahceli, Y. & Saba, Y. (2023). Saudi wealth fund to raise $5.5 billion with second green bond sale. Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/saudi-arabias-pif-selling-three-tranche-dollar-green-bonds-2023-02-07/

Barrett, E. (2021). The 2022 Beijing Olympics will ban all spectators—except Chinese fans who meet ‘specific requirements. Fortune. Retrieved from: https://fortune.com/2021/09/30/beijing-winter-olympics-2022-china-spectators-ban-covid-fans/

Beall, J. LIV Golf attorneys reveal league generated ‘virtually zero’ revenue in 2022. Golf Digest. Retrieved from: https://www.golfdigest.com/story/liv-golf-revenue-2023#:~:text=The%20news%20that%20LIV%20Golf,event%20purses%20and%20tournament%20buildout.

Brannagan, P. M., Grix, J. & Lee, D. (2019). Sports Mega-Events and the Concept of Soft Power. Entering the Global Arena, 23-36.

Brannagan, P. M., Giulianotti, R. (2018). The soft power-soft disempowerment nexus: the case of Qatar. International Affairs, 94(5), 1139-1157.

Brown, L.D. (2010). The Political Face of Public Health. Public Health Reviews, 32(1), 155-173.

Brownell, S. (2012). Human rights and the Beijing Olympics: imagined global community and the transnational public sphere. The British Journal of Sociology, 63(2).

Bryder, T. (2001). Motivational Approaches to the Study of Political Leadership. Översikter och meddelanden, 104(2). Retrieved from: https://journals.lub.lu.se/st/article/view/2203

Buigut, S. & Kapar, B. (2020). Effect of Qatar diplomatic and economic isolation on GCC stock markets: An event study approach. Finance Research Letters, 37.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1544612319304921

Byers, J. (2022). LIV Offering Richest Purse in Golf History. Front Office Sports. Retrieved from: https://frontofficesports.com/liv-offering-richest-purse-in-golf-history/

Cabinet Office Japan. (2018). The Final Report Development of Human Resources for Cool Japan (Abstract). The Cabinet Office of Japan. Retrieved from: https://www.cao.go.jp/cool_japan/english/pdf/published_document8.pdf

Campbell, C. (2016). China Wants to Become a ‘Soccer Superpower’ by 2050. Time Magazine. Retrieved from: https://time.com/4290251/china-soccer-superpower-2050-football-fifa-world-cup/

Campbell, C. (2022). ‘It’s Rare To See Change Happen at This Pace.’ A Global Backlash Is Forcing Qatar to Treat Migrant Workers Better. Time. Retrieved from: https://time.com/6240955/qatar-world-cup-migrants-labor-reforms/

Chan, J. (2017). More Than Just A Game: The Soft Power Politics of Sports and the 2018 Olympic Games. The McGill International Review. Retrieved from: More Than Just A Game: The Soft Power Politics of Sports and the 2018 Olympic Games – MIR (mironline.ca)

Chen, S. & Doran, K. (2022). Using Sports to “Build It Up” or “Wash It down”: How Sportswashing Give Sports a Bad Name. Findings in Sport, Hospitality, Entertainment, and Event Management, 2(3).

Clarey, C. (2014). In 2019 World Track Championships, Qatar Adds Second Sports Jewel. The New York Times.Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/19/sports/qatar-picked-to-host-2019-world-track-championships.html

Colgan, J. (2023). After viewership dip, LIV Golf has quietly stopped reporting TV ratings. Golf. Retrieved from: https://golf.com/news/liv-golf-quietly-stopped-reporting-tv-ratings/

Colorado State University (2023). Using content analysis. CSU. Retrieved from: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=61

Considine, M. (2023). Flush with cash, the Middle East is ramping up investment in soccer as a soft power push. CNBC.Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/13/soccer-uae-saudi-arabia-and-qatar-ramp-up-sports-investment.html

Crabtree, J. (2016). China’s goal to score some top soccer talent from the West. CNBC. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2016/08/09/chinas-buying-of-top-international-football-players.html

Craig, M. (2022). The Money Behind The Most Expensive World Cup In History: Qatar 2022 By The Numbers. Forbes.Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/mattcraig/2022/11/19/the-money-behind-the-most-expensive-world-cup-in-history-qatar-2022-by-the-numbers/?sh=3240881abff5

Cracry, D., Fam, M. & Tarigan, E. (2022). Across vast Muslim world, LGBTQ people remain marginalized. Associated Press. Retrieved from: https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-africa-religion-europe-05020d7baa9f0d5f0b3088e80d0797e9

Darwich, M. (2018). ‘The Saudi intervention in Yemen: struggling for status. Turkey Insight, 20 (2), 125-141.

Democracy Index. (2009). The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy 2008. Economist Intelligence.Retrieved from: https://graphics.eiu.com/pdf/democracy%20index%202008.pdf

Democracy Index. (2023). Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine. Economist Intelligence. Retrieved from: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2022/

Dun, S., Mejova, Y., Memon, S. A., Pillai, R. K., Rachdi, H. & Weber, I. (2022). Perceptions of FIFA Men’s World Cup 2022 Host Nation Qatar in the Twittersphere. International Journal of Sport Communication, 15(1): 1-10.

D’Urso, J. (2021). Newcastle takeover: Why PIF and the Saudi state are the same thing. The Athletic. Retrieved from: https://theathletic.com/2886837/2021/10/14/newcastle-takeover-why-pif-and-the-saudi-state-are-the-same-thing/

Elsborg, A. (2023). The expansion of Saudi investments in sport: From football to esport. Play the Game. Retrieved from: https://www.playthegame.org/news/the-expansion-of-saudi-investments-in-sport-from-football-to-esport/

Fast Company Staff. (2023). Is tourism soaring in Qatar after World Cup 2022? Yes, there’s 347% increase. Fast Company Middle East. Retrieved from: https://fastcompanyme.com/news/is-tourism-soaring-in-qatar-after-world-cup-2022-yes-theres-347-increase/#:~:text=Is%20tourism%20soaring%20in%20Qatar,of%20tech%2C%20business%20and%20innovation.

Fourie, J & Santana-Gallego, M. (2011). The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1364-1370. Retrieved from: The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals – ScienceDirect

France-Presse, A. (2023). Will Qatar’s bid for Manchester United force sale of PSG? The Score. Retrieved from: https://www.thescore.com/eng_fed/news/2579752#:~:text=QSI%2C%20a%20subsidiary%20of%20the,Qatar%20can%20project%20soft%20power.

Fraschilla, F. (2017). Top 12 basketball leagues in the world outside the NBA. ESPN. Received from: https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/18470135/fran-fraschilla-rankings-world-top-12-basketball-leagues-nba

Fruh, K., Archer, A., & Wojtowicz, J. (2023). Sportswashing: Complicity and Corruption. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 17(1).

Fowler, G. A. & Meichtry, S. (2008). China Counts the Cost of Hosting the Olympics. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB121614671139755287

Ganji, S. K. (2022). The Authoritarian’s Guide to Football. Journal of International Affairs, 74(2), 37-64.

Ganji, S. K. (2023). The Rise of Sportswashing. Journal of Democracy, 34(2), 62-76.

Geurin, A. N. & Narine, M. L. (2020). 20 Years of Olympic Media Research: Trends and Future Directions. Front Sports Act Living, 2.

Gerring, J. & Seawright, J. (2008). Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(294).

Gerring, J. (2017). Case study research: Principles and practices (2ed ed.). Cambridge University

Gil, D. (2023). Qatar wants to follow Manchester City owners’ footsteps. Mundo Deportivo. Retrieved from: https://www.mundodeportivo.com/us/en/soccer/20230109/30763/qatar-wants-to-follow-manchester-city-owners-footsteps.html

Global Times. (2022). China to invest $331 million to build 185 sports venues for public use: NDRC. Global Times.Retrieved from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202202/1252384.shtml#:~:text=China%27s%20National%20Development%20and%20Reform,infrastructure%20and%20services%20to%20boost

Godhinho, V. (2022). Qatar tourism has a robust post-World Cup growth strategy in place. Business Traveller. Retrived from: https://www.businesstraveller.com/features/qatar-tourism-has-a-robust-post-world-cup-growth-strategy-in-place/

Grix, J. & Houlihan, B. (2013). Sports mega-events as part of a nation’s soft power strategy: The Cases of Germany and the UK. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 16(4).

Guzman, C. D. (2022). What the world can learn from China’s COVID-19 rules at the winter Olympics. Time. Retrieved from: https://time.com/6149800/beijing-2022-covid-19-olympics/

Hafiz, T. Z. (2023). PIF embraces the sky with Riyadh Air. Arab News. Retrieved from: https://www.arabnews.com/node/2271141/pif-embraces-sky-riyadh-air

Hershberg, G. J. (2019). New Russian evidence on Soviet-Cuban relations, 1960-61. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Retrieved from: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/cwihp_working_paper_90_new_russian_evidence_on_soviet-cuban_relations_1960-61.pdf

Hindustan Times. (2018). Asian Games TV viewership better than FIFA World Cup, Wimbledon. Hindustan Times, New Delhi. Retrieved from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/asian-games- 2018/web-sep7-asiangames/story-OIdmVX05HO3vDI0S8hsNtN.html

Holocaust Encyclopedia. (2023). The Nazi Olympics Berlin 1936. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved from: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nazi-olympics-berlin-1936

HRQ. (2008). Appeasing China – Restricting the rights of Tibetans in Nepal. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/07/24/appeasing-china/restricting-rights-tibetans-nepal

HRW. (2022). Qatar: Security forces arrest, abuse LGBT people. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/24/qatar-security-forces-arrest-abuse-lgbt-people

IMF. (2023). GDP per capita, current prices. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

Infante-Rivard, C. & Cusson, A. (2018). Reflection on modern methods: selection bias—a review of recent developments. International Journal of Epidemiology.

InsideFIFA. (2023). One Month on: 5 billion engaged with the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022. FIFA. Retrieved from: https://www.fifa.com/tournaments/mens/worldcup/qatar2022/news/one-month-on-5-billion-engaged-with-the-fifa-world-cup-qatar-2022-tm

Kelts, R. (2006). Japanamerica: How Japanese pop culture has invaded the U.S. Palgrave Macmillan.

Keys, B. J. (2006). Sport, the state, and international politics. In globalizing sport. Harvard University Press.

Khan, S. (2020). Saudi Vision 2030: New avenue of tourism in Saudi Arabia. Studies in India Place Name, 40(75). Retrieved From: https://www.academia.edu/43593422/Saudi_Vision_2030_New_Avenue_of_Tourism_in_Saudi_Arabia

LeBlanc, P. J. (2021). Sweeping the soft power podium: A quantitative and qualitative analysis of Olympic soft power’s Impact on the host nations international image. Naval Postgraduate School Monterey CA. Retrieved from: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1164945

Leung, Xi Yu; Wu, Bihu; Xie, Fang; Xie, Zhihua; and Bai, Billy (2016). Overseas tourist movement patterns in Beijing: The impact of the Olympic Games. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally. 1.

Lewis, T. (2015). Excercises in soft power and cultural diplomacy: The cultural programming of the Los Angeles and London Olympic Games. The Ohio State University. Retrieved from: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=osu1430946430&disposition=inline

Li, X., Zhang, W., Zhang, W. et al. (2002). Level of physical activity among middle-aged and older Chinese people: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 20, 1682.

Lo, J. (2021). Saudi Arabia aims for 50% renewable energy by 2030, backs huge tree planting initiative

Mai, H. J. (2021). Saudi Arabia and China are accused of using sports to cover up human rights abuse. NPR. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2021/11/29/1058048696/saudi-arabia-formula-1-china-olympics-human-rights-sports

Maizland, L. (2022). China’s repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-xinjiang-uyghurs-muslims-repression-genocide-human-rights

Martin, A. (2023). Big twist as Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad al Thani eyes up West Ham takeover with $960 million fortune. Hammers News. Retrieved from: https://www.hammers.news/news/big-twist-as-sheikh-jassim-bin-hamad-al-thani-eyes-up-west-ham-takeover-with-960-million-fortune/

Mathews, S. (2021). As Hajj winds down, Saudi Arabia ramps up big tourism plans. AlJazeera. Retrieved from: As Hajj winds down, Saudi Arabia ramps up big tourism plans | Tourism News | Al Jazeera

Meeuwsen, S. & Kreft, L. (2022). Sport and politics in the twenty-first century. Taylor & Francis Online. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2022.2152480

Meng, L. & Neto, V. (2022). Beijing: the world’s first dual Olympic city. Olympics. Retrieved from: https://olympics.com/en/news/100-days-to-go-beijing-worlds-first-dual-olympic-city

Milanovic, M. (2019). The murder of Jamal Khashoggi: Immunities, inviolability and the human right to life, human rights law review. Forthcoming. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3360647

Milmo, C. (2008). 2008: The year a new superpower is born. Independent. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/2008-the-year-a-new-superpower-is-born-5337938.html

Mukund, S. (2022). What’s the IOC – and Why Doesn’t It Do More About Human Rights Issues Related to the Olympics? University of Connecticut Sport Management Program. Retrieved from: https://sport.education.uconn.edu/2022/02/22/whats-the-ioc-and-why-doesnt-it-do-more-about-human-rights-issues-related-to-the-olympics/

Muller, M. (2015). What makes an event a mega-event? Definitions and sizes. Leisure Studies 1-16. What makes an event a mega-event? Definitions and sizes (bham.ac.uk)

Næss, E. H. (2023). A figurational approach to soft power and sport events. The case of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022. Frontiers. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2023.1142878/full

NEOM. (2023). HRH Prince Mohammed Bin Salman Announces the Establishment of Trojena, the Global Destination for Mountain Tourism in NEOM. NEOM. Retrieved from: https://www.neom.com/en-us/newsroom/hrh-prince-announces-trojenaAmerican basketball players share tales of what it’s really like to play in China – ESPN

Neumann, T. (2017). What it’s really like for Americans playing basketball in China. ESPN. Retrieved from:

Noble, J., Massoudi, A., Smith, R., England, A. (2022). Saudi Arabia wealth fund commits $2.3bn to football sponsorships. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/ce556bac-30cc-49c6-b883-5cab67ce5379

Nye, J. S. (1990). Soft Power. Foreign Policy, 80, 153–171.

Nye, J. S. (2004). Soft Power. Political Science and Politics, 37(1), 49-53.

Offenhauer, P. (2005). Women in Islamic Societies: A Selected Review of Social Scientific Literature. The Library of Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.loc.gov/rr//frd/pdf-files/Women_Islamic_Societies.pdf

Olsen, A.B., (2022). A global map of Qatar’s sponsorships in sports. PlaytheGame. Retrieved from: https://www.playthegame.org/news/a-global-map-of-qatar-s-sponsorships-in-sports/

O’Donnell, C. (2023). A look at the history of boxing in Saudi Arabia. Arab News. Retrieved from: https://www.arabnews.com/node/2265891/look-history-boxing-saudi-arabia

OlympicTalk. (2022). Saudi Arabia to host 2029 Asian Winter Games. NBC Sports. Retrieved from: https://www.nbcsports.com/olympic/news/saudi-arabia-asian-winter-games-2029

Panja, T. (2023). China’s Soccer Experiment was a Flop. Now It May Be Over. The New York Times. Received from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/sports/soccer/china-soccer.html

Park, K., Koo, G. & Kim, M. (2023). The effect of UN resolution for Olympic Truce on peace based on functionalism. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 18(1), 107-125.

Pattisson, P., McIntyre, N., Mukhtar, I., Eapen, N., Bhuyan, M. O. U., Bhuttarai, U. & Plyari, A. (2021). Revealed: 6500 migrant workers have died in Qatar since World Cup awarded. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/feb/23/revealed-migrant-worker-deaths-qatar-fifa-world-cup-2022

Piastowski, N. (2023). Ian Poulter knew what he’d be gaining, losing with LIV ‘Full Swing’ Ep. 3 recap. Golf. Retrieved from: https://golf.com/news/ian-poulter-gaining-losing-liv-full-swing-ep-3-recap/#:~:text=With%20LIV%2C%20the%20money%20is,play%20is%20obviously%20an%20attraction.

Pinkston, D.A. (n.d.). Sports and Ideology in North Korea. Asia Society. Retrieved from: https://asiasociety.org/korea/sports-and-ideology-north-korea

Poindexter, O. (2022). Qatar Now Wants to Host 2036 Olympics. Front Office Sports. Retrieved from: https://frontofficesports.com/qatar-now-wants-to-host-2036-olympics/

Ramani, S. (2021). The Qatar Blockade Is Over, but the Gulf Crisis Lives On. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/01/27/qatar-blockade-gcc-divisions-turkey-libya-palestine/

Rashid, Y., Rashid, A., Sabir, S. S., Warraich, M. A. & Waseem, A. (2019). Case Study Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business Researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919862424

Reuters. (2022). IOC was not consulted in Saudi choice for 2029 Asian winter Games. Reuters.https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/ioc-was-not-consulted-saudi-choice-2029-asian-winter-games-2022-10-05/

Reuters Staff. (2012). Qatar to continue bidding for Olympic Games. Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-olympics-qatar/qatar-to-continue-bidding-for-olympic-games-idUSBRE8AE0VN20121115

Rizzo, L. (2023). PGA Tour agrees to merge with Saudi-backed rival Live Golf. CNBC. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/06/pga-tour-agrees-to-merge-with-saudi-backed-rival-liv-golf.html

Roberts, D. (2017). Qatar row: What’s caused the fall-out between Gulf neighbours? BBC News. https://web.archive.org/web/20190426094813/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-40159080

Romo, V. (2022). No medals for 2022 Beijing Olympics. The Games drew their lowest U.S. ratings ever. NPR.Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2022/02/22/1082461546/no-medals-for-2022-beijing-olympics-the-games-drew-their-lowest-u-s-ratings-ever#:~:text=No%20medals%20for%202022%20Beijing,their%20lowest%20U.S.%20ratings%20ever&text=Ashley%20Landis%2FAP-,Reports%20released%20Monday%20indicate%20there%20was%20an%20average%20total%20audience,Games%20in%20Pyeongchang%2C%20South%20Korea.

Salao, C. (2023) The Saudi Multi-Billion Dollar Investment in Global Sports Explained. TheStreet. Retrieved from: https://www.thestreet.com/lifestyle/sports/the-saudi-multi-billion-dollar-investment-in-global-sports-explained

Saudi Tourism Authority. (2022). Saudi Arabis is the fastest growing tourism destination in the G20. PRNewswire.Retrieved from: SAUDI ARABIA IS THE FASTEST GROWING TOURISM DESTINATION IN THE G20 (prnewswire.com)

Saudi Tourism Authority. (2023). Saudi a Tourism force to be beckoned with at Arabian Travel Market 2023. Saudi Tourism Authority. https://www.sta.gov.sa/en/news/arabian-travel-market-2023

Saudi Vision 2030. (n.d.). A Vision That Empowers Giving. Retrieved from

Shelley, E. (2022). 2022: The Year Of Sportswashing. Australian Outlook. Retrieved from: https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/2022-the-year-of-sportswashing/

Sin, J. (2022). Did the 2008 Olympic Games shape political perceptions of China? Res Publica. Retrieved from: https://respublicapolitics.com/articles/did-the-2008-olympic-games-shape-political-perceptions-of-china

Skey, M. (2022). Neologisms of (washing) in academic literature. Media, Culture & Society, 44(3), 343-360. doi:10.1177/10126902221136086

Slater, M. (2020). Exit China, enter the US. Who wants to own a European football club? The Athletic. Retrieved from: https://theathletic.com/1887653/2020/09/23/chinese-america-money-european-football/

Smith, L. (2023). Report of $20 billion Saudi bid to buy F1 was ‘speculation’: Sports minister. The Athletic. Retrieved from: https://theathletic.com/4324851/2023/03/19/report-of-20-billion-saudi-bid-to-buy-f1-was-speculation-sports-minister/

Staggers, J. (2023). Why is Saudi Arabia investing so much money into sports? The Snapper. Retrieved from: https://thesnapper.millersville.edu/index.php/2023/04/26/why-is-saudi-arabia-investing-so-much-money-into-sports

Storm, R. K. & Jakobsen, T. G. (2019). National pride, sporting success and event hosting: an analysis of intangible effects related to major athletic tournaments. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 1. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19406940.2019.1646303

Summerscales, R. (2023). Karim Benzema agrees $321m deal with Al-Itthiad but Cristiano Ronaldo will still be highest-paid player in Saudi Arabia for now. SI-FanNation Futbol. Retrieved from: https://www.si.com/fannation/soccer/futbol/transfers/karim-benzema-agrees-to-107m-salary-at-al-ittihad